Giveaway now closed.

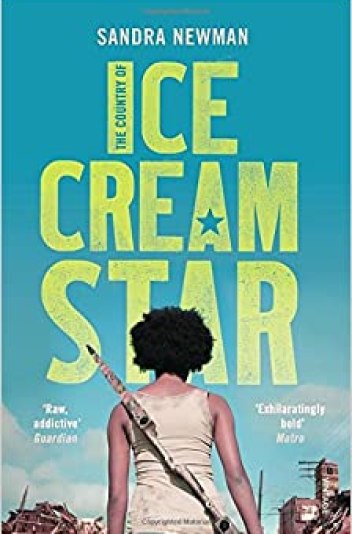

If you were following my Bailey’s Prize longlist reading, you’ll know there was one book on the list that I thought was extraordinary. That book was The Country of Ice Cream Star by Sandra Newman. (Click on the title to read my review.) The novel’s narrated by fifteen-year-old Ice Cream Star in the Nighted States. White people have died out from a disease called WAKS and the remaining black people have truncated lives, contracting posies and dying when they’re eighteen or nineteen. As the novel begins, Ice Cream Star’s brother has the disease and when she discovers there might be a cure, she sets out to find it.

Two things make the novel quite different from your average slice of literary fiction. The first, as I’ve already mentioned, is that the world of the novel is peopled almost entirely with black characters. The second is that Newman’s written the whole book in a futuristic version of African American Vernacular English.

After I’d finished reading the book, I spent days thinking about it so I was absolutely thrilled when Sandra Newman agreed to answer some questions about the writing of it. If all this makes you want to read the book – and I so hope it does – there’s a chance to win one of five copies after the interview.

Where did the initial idea for The Country of Ice Cream Star come from?

I started writing the book in a period when I was struggling with bereavement; three of my closest friends had died. Two were male friends, who had been like brothers to me for years, so Ice Cream’s relationship with her brother comes directly from that feeling of loss. And the whole idea of the book – which is kind of a Gilgamesh story about someone who can’t accept mortality, and goes forth to defeat Death – comes from my inability to accept the death of these friends. I wanted to write a book in which you could have that feeling, and do something about it, and ultimately win.

So I came up with the world in which everyone dies of a disease when they’re still teenagers, and the heroine who refuses to accept that, and goes on a quest to find a cure for the disease.

How did you go about creating the voice of Ice Cream Star (and the groups who live in Massa) and how did you sustain that for an entire novel?

I didn’t initially intend to write the book in an invented patois. But when I started to write the book, it had to be set in a future world, and I wanted to the voice to feel absolutely real. I’ve always been the kind of writer (and reader) who needs a story to be completely convincing. When I was writing the book in standard English, I just couldn’t believe in it. A hundred years had passed. Obviously English would have changed in that time, especially if there were no schools and no media, and the language was only being spoken by children and teenagers.

So from there, the language ended up being informed by African-American English. I’ve given a lot of reasons for this, but the bottom line is just that it’s my favorite English, and probably objectively the best English going. It also gave me not only a model for innovation in the vocabulary, but a starting point for innovation in the grammar. And finally, most people are familiar with it to some degree, so readers have a starting point for understanding it.

Once I had the flavor of African-American speech in the language (and don’t get me wrong – it’s not African-American Vernacular English as spoken now, but it’s obviously strongly influenced by it) it felt like the characters should be black. Or, put another way, why shouldn’t they be black? I mean, it became a choice to make them anything but black.

And then, as soon as I thought of them as black, the book came to life in the most incredible and inexplicable way. It began to write itself. I don’t know why this is, since the book isn’t about race – or it’s only very occasionally, tangentially, about race. It just suddenly felt like a real world I had discovered, rather than an imaginary world I was inventing. Everything fell into place.

I was very aware that this was a controversial thing to do, as a white person. I thought about it a lot, and questioned my position, and etc But after a while, I couldn’t really help writing the book that way because it worked. Also, the characters very quickly became real people to me, who demanded to be written about as they were.

Sustaining it for an entire novel was time-consuming, but incredibly rewarding. In fact, I now find it a little sad writing in normal English, because it’s just not possible to be as inventive. And, just as with any foreign language, there are words in Sengle English for which there are no exact equivalents in contemporary English, so I sometimes end up feeling like my normal speech is an inadequate translation.

Did anyone try and dissuade you from writing the book in dialect? I’m thinking particularly from a commercial standpoint. I assume most readers of literary fiction are Standard English speakers so it deliberately distances, if not alienates, them. It would also create an interesting challenge for translators if it were to be translated into other languages.

There were two people who tried to dissuade me. One was a wonderful friend of mine, who had originally suggested that I try to write a young adult novel (he’s a YA author) as a way of possibly making more money from my writing. He was worried about me because I was always so broke. And, to help me do this, he put me together with his agent, who handles YA, and is very, very successful; the kind of person who does million-dollar deals.

So the agent was very excited about the concept of The Country of Ice Cream Star as a young adult book. (It ended up not really being a young adult book, but at that time it was only 30 pages long, and after all, the heroine is fifteen.) He was not, however, excited about trying to sell a book in an invented patois. And my friend, who had been so concerned about my finances, gently tried to get me to see the possibilities of writing the book in standard English. He told me confidentially that the agent had mentioned the sum of $400,000 as what he thought he could get for the book, if it were only written in standard English.

Well, I said no. Which is kind of startling to me, looking back. And I hadn’t yet shown the book to anyone else, so I had no idea if anyone else would want it.

So I ended up selling the book with another agent (the wonderful and brilliant Victoria Hobbs) for a healthy amount, but not for anything like $400,000. I mean, I think it’s a much, much better book than it would have been in standard English. It couldn’t have been anything like as beautiful.

There’s a great statement that’s been doing the rounds on Twitter for a while now: ‘@fqubed: Dystopian lit is: “what if the government got so powerful that all the bad stuff that’s already happening ALSO HAPPENED TO WHITE PEOPLE?” ‘ You’ve taken that to its extreme in that the white people have been wiped out in the USA. What do you want people to take away from the book in terms of the current situation with regards to race?

Well, there are two answers to that question. As far as people of color are concerned, I just hope they like the book. I mean, I hope black readers can get some pleasure from a fictional America where the norm is to be black, and everyone’s black and it isn’t even an issue, regardless of the fact that the book was written by a white person. But do I have anything to tell them about the current situation with regards to race? I highly doubt it.

As far as white people are concerned, I hope it’s somehow a little mind-altering to spend time in that world where it’s the norm to be black, and virtually all the people – brilliant and stupid, selfish and altruistic, brave and cowardly, whatever and whatever – are black. You know, a world where black = human, and that’s the end of the story.

I do find that often in contemporary narratives, the blackness of a character ends up being their chief feature. Their story is about blackness, and even when the intention is completely good, well, these are human beings with an infinite range of complexity. Black lives are not just about race relations.

But it’s still hard to successfully market a book about (or by) a black person unless it’s about slavery or the Civil Rights movement or (in recent years) microaggressions. This is all about white audiences, of course, and their expectations. I don’t mean to demonize white audiences; but, that’s the history we’ve all grown up with. So I hope that after reading my novel, it might become more possible for some white readers to pick up a book by Jesmyn Ward or Percival Everett and be thinking, “Wow, this looks like a great book,” instead of, “Maybe I should read a book by a black person.”

Still, I don’t think there’s all that much that you can do with one novel. You just add your grain of sand to the gigantic pile of grains of sand that make up a culture, and hope to God you’re adding it in the right place.

Religious and political corruption is rife in the novel; was this intended to reflect current society? Regardless of the make-up of a society do you think there will always be someone who takes power and misuses it?

It was really just intended to reflect any society. So far, we haven’t created a society which is free from power relations, and the abuse of power relations. So, in The Country of Ice Cream Star, we see a series of different societies, and while some are much more corrupt than others, they’re all subject to human frailty. And because human frailty tends to take on similar forms throughout history, there are inevitably echoes of current society.

I was also trying to depict a heroine who is sharp enough to see the hypocrisy and corruption around her, and doesn’t waste time being upset by it, but just tries to use whatever she can to change things for the better. So she’ll work with the corrupt leader or she’ll work with the misguided zealot; she’s just trying to save her people by any means necessary. That was important to me because I was thinking about what makes someone a hero. I think this might be the most important trait in a hero, that willingness to see the evil in the world and just use it like any other tool to eradicate some of the evil in the world.

Ice Cream Star is a very different hero from the likes of recent dystopian protagonists – Katniss Everdeen, Beatrice Prior, Cassia Reyes, for example. There’s a physical and emotional maturity to her that you might not expect in a fifteen-year-old. Is that just a reflection of the situation she’s in or is there also a link to people currently coming-of-age in difficult circumstances?

I think it’s actually a trait of a lot of teenagers. Ice Cream is really childish one moment, and incredibly mature and savvy the next. At that age, a lot of people – especially very smart people – are like that. She’s also lived with a lot of responsibility from a very young age, so she naturally takes up new responsibilities without thinking about it. You can think of that as difficult circumstances, but it’s also an opportunity. I think contemporary teenagers don’t get to show what they could potentially do, if they were allowed to have adult responsibilities.

In the Middle Ages and earlier, it was not uncommon for teenagers to lead men in war (the most notable example being Alexander the Great). And in our grandparents’ generation, it was unremarkable for people to marry and become parents at eighteen. Obviously, sometimes this ended in disaster. But sometimes it ended with the conquest of Asia, or with our parents (in those case where our parents turned out be well-adjusted happy people).

How does it feel to be longlisted for the Bailey’s Women’s Prize for fiction?

It just feels incredibly lucky. I mean, I personally love The Country of Ice Cream Star. I think it’s the best book ever, and I can’t help doubting the judgment of anyone who doesn’t love it as I do.

But there are many truly great books that never get longlisted for anything. Judges are human beings, so they have limited time and their own personal likes and dislikes which inevitably affect their choices. And. in my view, should affect their choices, or else what are we even talking about? Virginia Woolf, for instance, was offered the chance to publish Ulysses, and turned it down.

Maybe that’s a little off the point (the point being that I was incredibly, jumping-up-and-down, happy when I got the news) but I know so many struggling (and deserving) authors who just can’t catch a break. So I always think of them whenever I have a piece of luck. (Keeping in mind, of course, that The Country of Ice Cream Star is still literally the best book ever.)

What are you working on now? Can you tell us anything about it?

I’m primarily working on a sequel to The Country of Ice Cream Star, which is partly because the story isn’t properly finished (which you can kind of tell from the ending) and partly because I love Ice Cream and her world too much to let go of it.

But I often work on two projects at one time, so I’m also trying to cook up another book to work on. I haven’t settled on anything quite yet, and the possible books are really various: there’s a post-apocalyptic novel about a ballet company; a contemporary novel about a friendship; a non-fiction book about sexual assault; a non-fiction book about math. My real problem is that I would like to write all these books immediately, and occasionally I lose all sense of time and think I can do exactly that.

And, of course, there are other days when I want to just get a job selling soft drinks on the beach. But I’d probably be terrible at that, anyway. I’d just keep getting distracted and giving people the wrong change.

My blog focuses on female writers; who are your favourite female writers?

Since I’ve already mentioned Jesmyn Ward, I’ll start with her. She won the National Book Award for Salvage the Bones, and she’s still, in my opinion, under-rated. Or at least, under-read.

Then there’s George Eliot, whose books I just read again and again.

I read all of the historical novels of Dorothy Dunnett, while writing The Country of Ice Cream Star, and there’s really nothing else like them.

And, to throw in a science fiction writer, since I am part of that fandom, I’m a huge fan of James Tiptree, Jr. (Alice Sheldon). It’s sort of a hobby of mine to find ways of making people read her truly astonishing alien-life-form love story Love Is the Plan the Plan Is Death.

A huge thank you to Sandra Newman for the interview. How thrilled am I that there’s going to be a sequel?

If you’d like to find out for yourselves why I’m so enamoured of this book, Vintage have kindly given me FIVE copies to give away. All you need to do is leave a comment below, begging me to release them from my grasp! I kid. Leave a comment below and I’ll enter you into the draw. Worldwide entries are welcome. The competition will close at 5pm (UK time) on Friday 1st May. Winners will be chosen at random and informed as soon as possible after entries close.

Giveaway winners

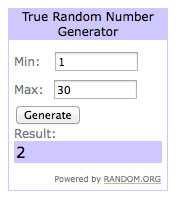

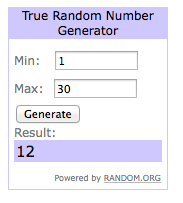

As usual, I’ve allocated everyone a number in order of entry, as follows:

1 – Snoakes

2 – Marina Sofia

3 – Claire Fuller

4 – Helen

5 – Lisa Farrell

6 – Kath

7 – Nina Pottell

8 – Paola Ruocco

9 – Jennie Finch

10 – Alison Layland

11 – Rebecca Foster

12 – k

13 – Chyma

14 – Elle

15 – Aisling Gheal

16 – Lydia Syson

17 – Alice

18 – Debbie Rodgers

19 – Naomi

20 – Crimeworm

21 – JAD

22 – Katie

23 – Claire Thinking

24 – Zarina

25 – Judith

26 – Liz Smith

27 – Tina M Holmes

28 – Greythorne

29 – allyblue22

30 – Cathy746Books

And the winners are…

Congratulations Marina Sofia, k, Nina Pottell, Tina M Holmes and Alice. Check your emails. Thanks to everyone else for entering.

Leave a Reply